“He turned away into the darkness and she heard his voice above the ripple and roar of the waves. ‘Okatsu-san, Okatsu-san. Don’t forget me.’

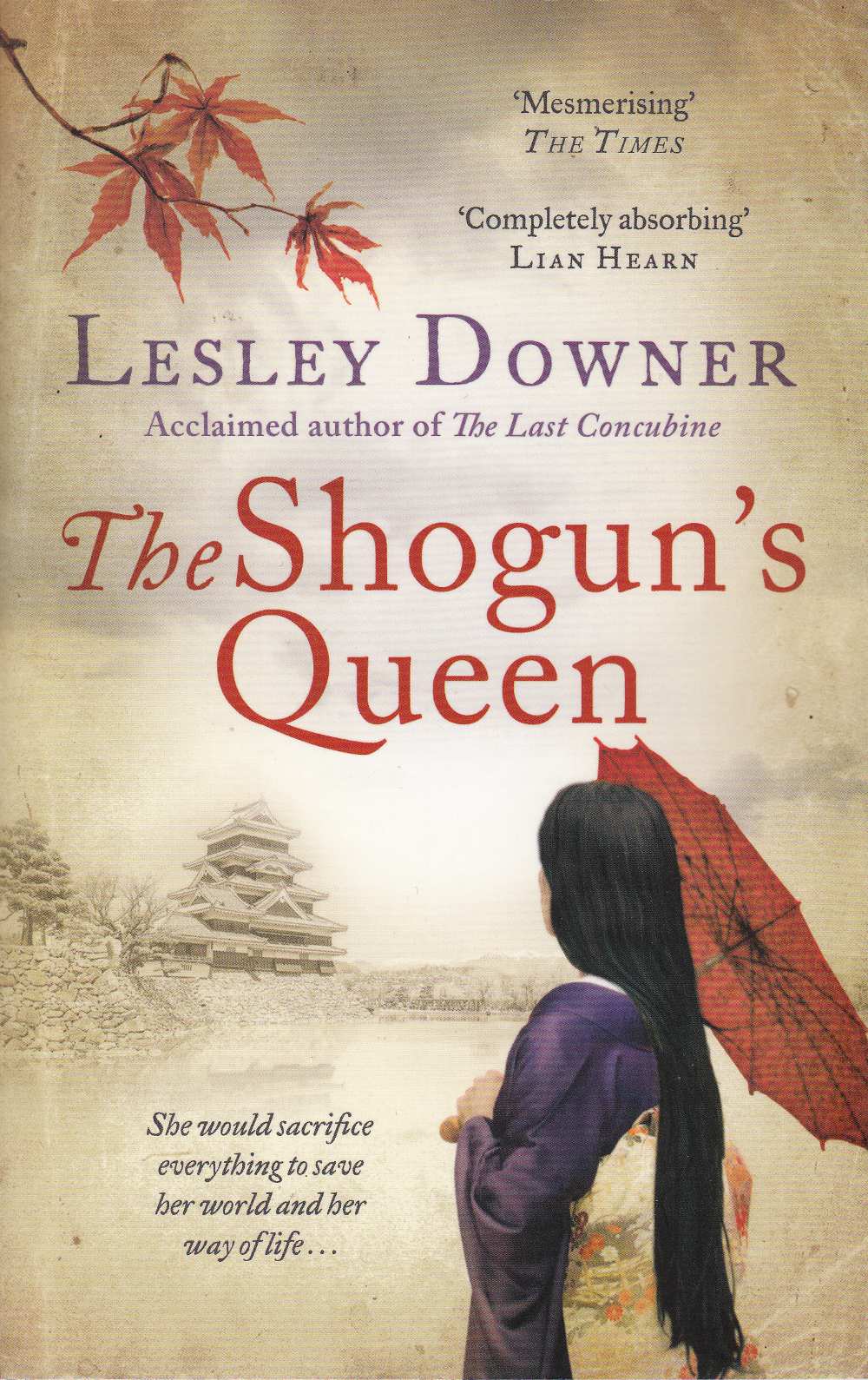

The Shogun’s Queen

She gave a sob and closed her fingers around the hilt of the dagger and said softly, ‘I won’t, I swear it. I won’t.’”

By שנילי Eli Shany אלי שני (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

How do you fall in love when there is no word for ‘love’ in your language?

The Shogun’s Queen is a love story set in a world in which there was no word for ‘love’, no concept of ‘love’.

I was amazed to discover that this was the case in Japan all the way up to the mid-nineteenth century, when my story is set. There was a word for ‘desire’, a word for ‘lust’. But there was no word for that madness that sweeps you off your feet when you’re least expecting it, that inspired knights in armour to take a lady’s glove into battle and drove gentlemen to drop to one knee and beg a lady to marry them, that sent couples rushing off to Gretna Green in defiance of their parents’ wishes.

It was not that Japanese didn’t fall head over heels in love. But to the government of the day love was so dangerous, so likely to threaten the order of society, that they banned it, made it illegal or at the very least contained it.

When people did fall in love they knew they were committing a crime or at the very least making a terrible mistake. It could only end badly. And that made it all the more fatally attractive. Love was the forbidden fruit.

Falling in love wasn’t something you expected and wanted to happen. No one looked for Mr or Miss Right, no one expected to meet the perfect person and settle down and marry.

Love and marriage didn’t go together like a horse and carriage. Love was to be feared. It was not a welcome, joyous thing but a dreadful curse.

Young people expected their parents to arrange a marriage for them and trusted them to find a suitable husband or wife. Usually you were allowed to say ‘No’. No one twisted your arm unless you were of such high rank that you were married off in a political marriage.

And people certainly didn’t expect to love their husband or wife. Love was not something a man felt for his wife. That would have been disrespectful. Respectable married women wouldn’t have dreamt of ‘tarting themselves up’. That was what geishas and courtesans did. All the women shown in woodblock prints wearing gorgeous flamboyant kimonos and with their hair studded with hairpins are ladies of the night, not respectable women.

Ordinary women didn’t hope for happiness but tranquillity. They assumed they would have children and would devote themselves to them. That was the purpose of marriage. Life was about doing your duty, about giving, not getting, doing what was required of you, not rocking the boat. It wasn’t about happiness, let alone love.

When people did fall in love, it came as a shock. You wouldn’t know what had happened, what was happening to you. And that made it all the more thrilling, that it was a forbidden experience. Even someone who’d always been well-behaved and obedient might be tempted to reject everything and follow her heart instead of doing what she was supposed to do in a society where everyone followed the rules.

If you did fall in love you knew you would not be able to spend your life with the one you loved. You’d both be married off to other people. You would have to keep your love secret and spend your days silently yearning, maybe managing a secret meeting every now and then. Some people chose to run away and commit suicide together so they could be together in death. It was called ‘love suicide’ and to the Japanese of those days it was an extraordinarily romantic thing to do.

The Shogun’s Queen is about a woman who defies convention. She falls in love. And that brought her face to face with the dilemma that underlay all of Japanese society at that time. There was a terrible choice to be made. Should she do what she knew was right? Or should she follow her heart, abandon her family and duty and run away with this man she had fallen so passionately in love with?

For her the stakes were higher still. The fate of Japan itself was in her hands. And that’s the dilemma at the heart of The Shogun’s Queen.

Thanks to Nicole Sweeney. A version of this post was first published in her blog thebibliophilechronicles.com.